Ali Chahrour’s work, explores religion, love, loss, mourning, and memory through music, and the body. Although his performances are steeped in personal experience, he and his collaborators understand that our encounters with religion, love, and loss exist in larger cultural and political contexts. The context that is most important to Ali is his home country, Lebanon. All of his work has been (and will be) premiered in Beirut. “It’s my policy,” Ali told me; the work is personal on an individual and local level. We can all tap into the feeling, but fewer will know its roots.

Inspired by religion, love, the body, and the relationships between them all, Ali has gravitated towards local traditions of funerals, and lamentations ceremonies. عاشوراء (‘Ashoura), a holiday and ritual widely celebrated in Shi’ia Islam, is an occasion of lamentation, in honor of Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of the Prohpet Muhammed. “It’s not just a ritual… it’s a political act.” Ali feels this way about all situations of mourning. “The presence of the body [demonstrates] the value of poetry, and the beauty of sadness, passion, and identity.” Just as we celebrate our bodies, and celebrate with our bodies in life, in death too, the body maintains these relationships through different modes.

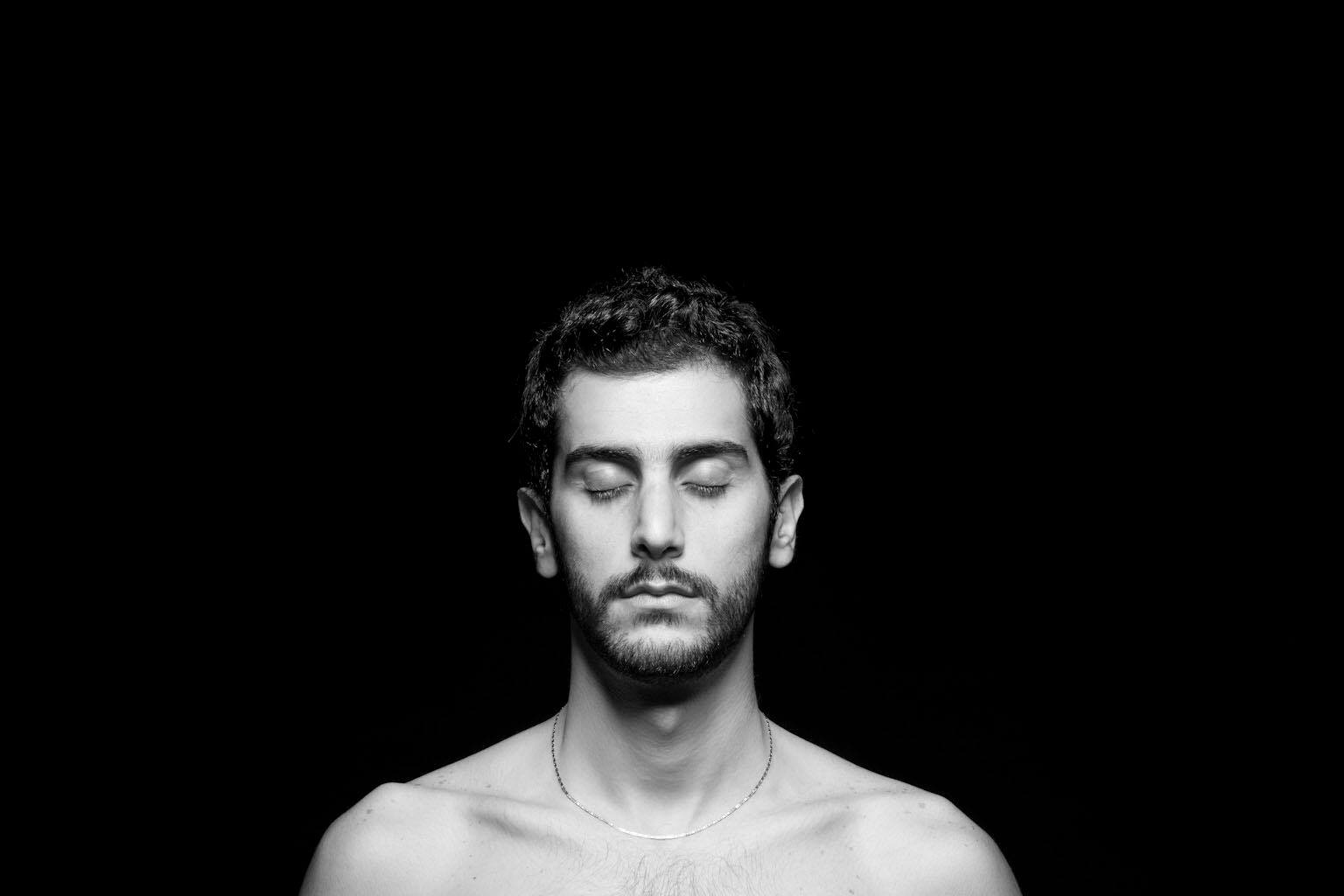

Ali and the team of Night. Photo by Thibault Montamat and Didier Olivre

“You can fall in love, not from love.” Ali experienced this through his Aunt Fatmeh, who lost her son, and spent more than 5 years looking for him across Lebanon and Syria. A “strong female figure” for Ali, Fatmeh embodied the “power of a mother, the power of a lover.” Fatmeh never found her son, but never stopped looking. A mother’s passion for her son, leads her to grieve his absence, so much so that she embarks on a pilgrimage to her love.

In an effort to capture the authenticity of these human experiences, Ali’s art making process is heavily guided by collaboration. “I don’t work with professional dancers,” Ali says, “[because of this, you gain] a real quality of humans and their bodies, rather than professional technicalities.” Testing the limits of the body, mind, and soul, the “clash between performers’ backgrounds is always interesting.” The goal is the “complicity of the individual;” the breakdown of borders between mind, body, and soul. “We ask questions with no answers… exploring the transformation of beauty, religion, religion and the body, love, and poetry [through local and larger Arab histories].” When their work eventually leaves Beirut, international audiences may “miss the local references, but will get something by being at a distance.” That distance, Ali believes, allows audiences outside of his home city to “watch with the body and think later.”

ليل (Night) is the first chapter in Chahour’s “Liturgy of Lamentations” trilogy. It is the examination of “the collapse of lovers and their bodies, and love itself.” Ali aims to give further insight into love, death, and bodies; the spaces between them all, and how we exist and move through them. Although it comes from a very personal place, and manifests through an even more intimate process, Night is an expression of universal human emotions that transcend physical and mental borders.

-Triston Tolentino ’18